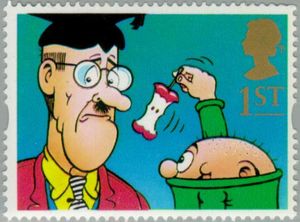

The Baldy-heidit

Maister

When I was at primary school, there was a little song going

round, sung approximately to the tune of My

Old Man’s a Dustman. The lyric was:

Oor wee

schule’s a guid wee schule,

It’s made o’

brick and plaister.

The only

thing that’s wrang wi’ it

Is the

baldy-heidit maister.

He goes to

the pub on a Saturday night,

He goes to

the kirk on Sunday.

He prays to

the Lord to gie him strength

Tae murder

the bairns on Monday.

I remember one of my pals, James Barker, singing this at a

school Christmas party. It caused much hilarity, and was considered audacious

in view of the fact that our headmaster at the time, Mister Bryce, who was

presiding over the celebrations, was bald. He took it all in good part. More of

Mister Bryce and his benign nature later.

**********************

Partly due to age, and partly to the job I do now, I find

myself more and more identifying not with the rebels, but with the authority

figures like the baldy-heidit maister. This is partly because experience has

taught me that they have precious little authority in these days when

governance is the watchword. I don’t know the official definition of

governance, but in research, it seems to mean people who have never done any

research laying down the law to those who have done research as to how it

should be done.

One of my duties at work is to facilitate at problem-based

learning sessions. These are small group gatherings of medical students in

which they are presented with an issue, usually a particular patient’s

symptoms. They are then asked to research the solution to the problem, and the

following week feed back their findings. It is acknowledged that this is not

the most efficient way of getting knowledge into students’ heads, but its

objective is to teach them to go to the library and educate themselves, in the

words of Frank Zappa.

In theory, the facilitator does not need to know anything

about the problem under study. Just as well. In the last few weeks, I have had

to facilitate sessions on the anatomy of the arm (or upper limb as we experts

call it), the anatomy of the leg (lower limb), and slipped disc in pregnancy. I

have no medical qualifications. What do I know about anatomy, other than The head bone connected to the neck bone?

Although I have my doubts about my contribution to these

PBL’s as they are called, I have to say that I am inspired to hear bright young

medical students rattle off the results of their homework. I wish I had been as

clever at age nineteen.

*************************

To come back to the subject of the baldy-heidit maister, I

remember my first two headmasters with some affection. My first primary school

was Saint Ninian’s in Bowhill. One day, when I was aged six, I think, I was

summoned to the office of the headmaster, Mister Flaherty. I was pretty sure I

hadn’t done anything wrong so wasn’t in trouble, but you never know... When I

got to his office, he had a chessboard set up on his desk and invited me to

take black. I had forgotten that Mister Flaherty was a drinking pal of my dad,

who was teaching him some chess gambits. Knowing that I too played chess,

Mister Flaherty had called me in to try these gambits out on me. I also think

that he deliberately let me win a couple of games.

Some years later, when I was in my teens, I related this

story to a pal of mine, who said he recalled a similar occasion in his primary

school career when he was detailed to report to the headmaster. Like me, he was

pretty sure he hadn’t done anything wrong so wasn’t in for a walloping, but all

the same, he was rather nervous. On arrival at the headmaster’s office, he was

informed that his younger brother had fouled his trousers and needed to be

taken home.

After a couple of years, we moved to Cowdenbeath, and there

the headmaster at St Bride’s was the previously mentioned Mister Bryce. In

addition to being in overall charge of the school and teaching the

eleven-year-old class, Mister Bryce also took the school football team to

fixtures, borrowing a Fife county education department minibus for the purpose.

St Brides was a very small school, with maybe a hundred and fifty kids aged 5

to 11 all told. As a result, Mister Bryce had to make the best of a fairly

small pool of talent for the football team. It was not unusual for us to lose a

match by a margin of ten or more goals. I think the worst we did was 21-1. I

can’t remember who was the hero who pulled one back for us. I am reminded of

Charles M Schultz’s response to those who queried the losses that Charlie

Brown’s baseball team sustained. Schultz said that losing 30 to nothing was not

uncommon for the team in which he had played as a child.

It says something of my sporting skills that in this team

that often lost twelve-nil to a neighbouring primary school that I never

actually made it off the subs bench.

Despite being baldy, Mister Bryce was unusually aware of

issues which would not come to the fore in society for another couple of

decades, including racism and sexism. It was clear he was uncomfortable with

the sectarian atmosphere of lowland Scotland at the time, and he could on

occasions show some quite courageous irreverence for a catholic school

headteacher. Mind you, I also recall him coming out to the playground and

leading us in prayers on the day of the Aberfan disaster.

In later life, I read JL Carr’s The Harpole Report, a brilliantly funny book about a teacher

thrust into the headship of his little primary school, and at almost every

event described, was reminded of Mister Bryce. In particular, I recall Carr’s

quote in relation to the importance of religious education: ‘God loves

mathematics well taught.’

JL Carr had worked in the USA and had served in the war as

an RAF intelligence officer, and Mister Bryce had similar horizons beyond the

little town which his school served. He emigrated to Canada around the same

time that I moved up to secondary school.

**************************

The above doesn’t have any moral or message. In

compensation, let me quote one of my clinical colleagues, a real doctor, not a

phony like me: ‘You teach to learn.’

Comments

Post a Comment